Australian Succulents

Attila Kapitany

Edible Succulent Plants

We have plants and seeds of edible succulent plants available on this website, just follow the prompts below or explore the left menu -

Also check our Ebay store, link on Home Page. Or go to book sales where a book and seeds dedicated to edible succulents can be found. More ...

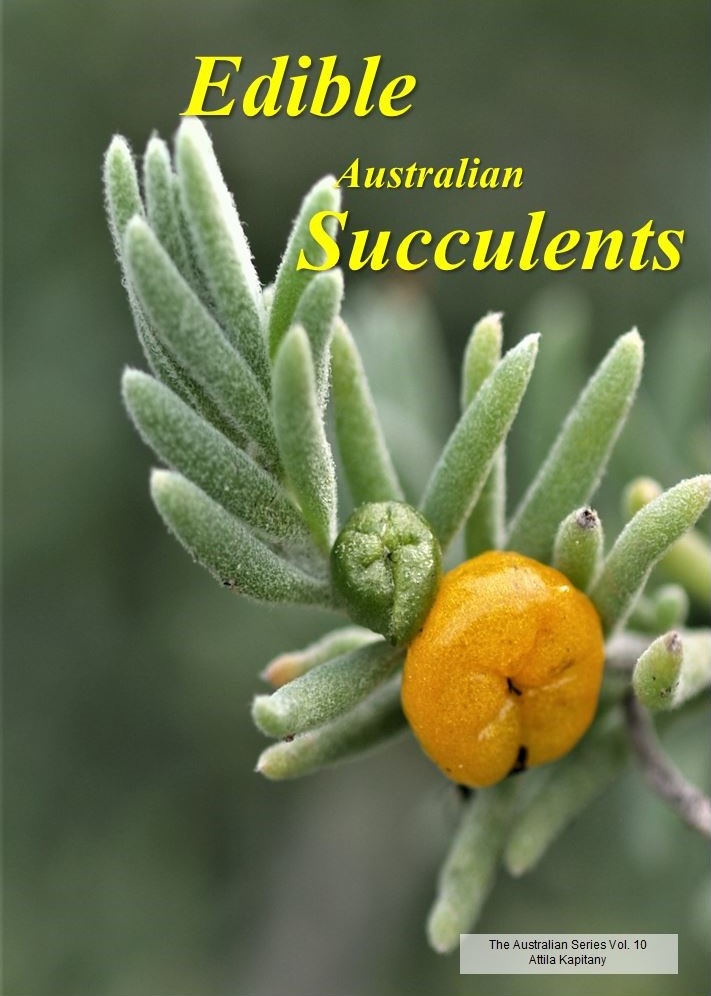

May 16, 2020 update: it has taken some years to put together new data about new and interesting Australian succulent plants that are edible. While there is some very old research about some edible succulent plants detailed below in this website, we have since been saving and collating all the latest and best data for a small printed book. We are also very excited to be offering information and seed of many new edible succulent plants that most people have never seen or heard of before. This book is titled Edible Australian Succulents and is jammed full of interesting information that is found no where else (online or otherwise). More ...

Here is a short 3 minute slideshow of native succulents (most of which are edible) all in our display garden.

Here is another shorter slideshow of native Calandrinia in habitat and the emus that eat them! This is one of my favourite native succulents (edible).

Apart from humans, almost all native and introduced herbivores and omnivores eat Calandrinia readily. If searching for such small plants proves too hard in arid places like this, then follow animal tracks and they eventually will lead you to water... in the form of Calandrinia. In fact in arid parts of the continent emu chicks rely almost entirely on this plant for their first 6 weeks. In the vicinity of the Calandrinia growing here, it was interesting to note an abundance of insects present, which are also a food source for emus.

Ethnobotany

Dr Beth Gott, Adjunct Research Fellow, Monash University, Melbourne, is one of Australia's leading experts on indigenous food plants.

Over the last 15-20 years or so I had various phone chats and emails with Dr Gott while she was at Monash University. As one of Australia's foremost authorities on the ethnobotany she has worked closely with various aboriginal communities to record indigenous plant uses, especially those that are regarded as food.

Dr Gott would routinely seek out plants or seed of various native succulents that I had, for her work. I would then ask her for her advice and expertise about aboriginal food plants that could also be regarded as succulent. I often had leading questions to get just the right answer I was after. Somewhat to her amusement she put up with my persistent questions.

I was discussing whether succulents were important in aboriginal culture, which at first Dr Gott would dismiss as minor, until further discussion led to a surprising reversal of her opinion on the matter. Finally Dr Gott confirmed that a plant's value as a food source is perhaps less important than a plant's value in providing moisture (water), often in dry and otherwise hostile environments. What was also agreed was that use of succulent plants as a food and water source are now unappreciated and very much under-utilised. Dr Gott adds: "Another use of succulents (mostly Carpobrotus species) by Aborigines was the sap as eyewash, and to soothe blisters and burns".

Some further points to consider.

After rare, sudden thunderstorms, or light showers, desert plants in such otherwise dry environments are able to collect/absorb available water quickly and efficiently to survive and grow. While many desert trees and shrubs grow relatively slowly, succulent plants will often grow rapidly, and not only drawing in water for immediate growth surges, but also extra in reservoirs to save for continual growth for weeks or months after the last rainfall. This survival strategy is only a small part of a larger complex picture, but I wish to focus on the fact that a shrivelled succulent in a dry desert (after drought) is often barely growing or alive at all. But after sufficient moisture from rain, such plants draw up more water than they need and they store it, and this becomes increasingly obvious as they become more turgid or succulent (as their level of ‘succulence, within the leaves, stems or roots increases). Indigenous people know that these plants that appear more succulent have moisture reserves that they can access when other sources of water are not available.

In a desert environment, when the rains have stopped and the ground water is not readily available or accessible to humans, succulent plants filled with water reserves can become essential for human survival. Through hot dry annual summers, there is always water available in succulent plants that grow in or near dried up river beds. Plants with succulent leaves are the most abundant type of useful plant that can be found throughout much of the year. If and when these plants slowly shrivel, dry or die following dry seasons or drought, then there are usually other types of succulent plants that have shorter succulent stems that can typically last longer and be available longer for their water reservoir. During the very driest months of the year or during extreme drought many formerly obvious succulent plants may be totally absent above ground; however some species survive by having very succulent roots, often tuberous and deep in the ground. Succulent plants with succulent roots can keep their water reservoir in cooler ground that also is protected from hot drying winds. Water reserves in succulent plant roots were a major component of aboriginal food and water, hence survival in desert regions.

I have travelled to remote dry Australian habitats where I have followed emu tracks and subsequently come upon thousands of small succulent Calandrinia. On another occasion I explored the boundary of an inland salt lake where I came across numerous species of plants where the only indication of plant life was dead dry sprigs of leaves etc. A small dig beneath each revealed sweet tasting succulent bulbs and tap roots. It was a very hot dry day of over 38'C, with the ground surface blistering hot yet digging to over 10 cm in depth and it was surprisingly cool. Some Calandrinia I have dug from roadside embankments have been held over my mouth crushed with my fingers to have almost clear cool water dribble into my mouth. (See slideshow above the article).

Succulent foliage in Australia has often been consumed by humans through history. It needs to be pointed out however that many of these plants have chemicals in them that if consumed in sudden quantity can also cause severe sickness. It is common knowledge that Tetragonia species and Portulaca species contain oxalic acid, which in high concentrations is harmful. It is also common knowledge and regular practice for chefs to blanch, or boil out much of the acid content. Simply cook like spinach for Tetragonia tetragonoides (Warrigal Greens). Even common spinach has high levels of oxalic acid, so eating large amounts raw can cause severe stomach illness. I want to stress that fresh new shoots of succulent plants after rain will have the lowest levels of oxalic acid within. The level of oxalic acid in Portulaca oleracea is greatly diluted when the plants are young and plump with water. One would assume the foliage would be crisper and more palatable to eat. In fact, conversely, if you ate the same plant shoots after weeks without rainfall, they would be less palatable as there would be with less water internally and have a more concentrated build-up of oxalic acid within. Therefore the more rain and the more water available and stored make plants far more succulent and also edible in the raw state.

A different perspective on this topic. Wood is inedible, though some juvenile tree seedlings and juveniles can be edible. The genera Brachychiton and Adansonia are well known as having edible parts, especially young plants with thickened succulent roots. Obviously the greater the succulence levels in the plant tissue; the more easily it can be eaten.

Understanding when and where to find and use succulent plants in arid environments has been a significant part of aboriginal survival and culture, yet modern scientific interpretation has unfortunately overlooked some of the value here.

Many succulent plants were held in extremely high regard by aborigines. Evidence of this can be found with scientific references in our small publication titled the Australian series, on our website.

In conclusion I feel compelled to write about something that interests me and may interest and be helpful to others.

________________________________________________________________________________

Below are sample excerpts from an in depth article that is too long to produce in its entirety here, but we encourage you to read the whole article at its source.

Succulent Plant Diversity as Natural Capital

By Olwen M. Grace Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, UK © 2019 The Author, Plants, People, Planet ©New Phytologist Trust

(Short excerpts from this science paper)

The economic value of arid-adapted succulent plants will likely increase under anticipated climate change scenarios (Mora et al., 2015). Regions of high succulent species richness coincide with places where socio-economic vulnerability to climate change is greatest, and the indigenous flora in these overlapping zones will likely assume greater importance …

….This development is crucial to harnessing the potential value of succulent plants responsibly, without compromising the native flora where they are introduced ….

…..Water-storing tissue is among the most successful of drought adaptations in the plant kingdom. Xeromorphic succulent plants represent a large and diverse resource with extraordinary potential to mitigate the negative consequences of climate change in regions where interventions will be most needed.

__________________________________________________________________________

The information below was compiled in 2007/8 and since then considerable extra facts and anecdotes have come to us from a range of sources. Much of this additional information and other species not covered below are discussed in our more recent 'Australian Series' of booklets. In fact the most recent book, Volume 10 is totally dedicated to EDIBLE SUCCULENT PLANTS!

While many Australian succulent plants have a range of uses, some have been lost over time, so the list of Aboriginal traditional food plants in literature underestimates the full range of plants that were used prior to European settlement.

In more recent years Australian food plants, also called bush foods or ‘bush tucker’, including some naturalised species, have gained popularity as people seek out alternative food sources, a few of which are already highly regarded in gourmet cooking. (Both native and introduced plants are covered here.) Also see the page on seeds for availability and further information about edible species.

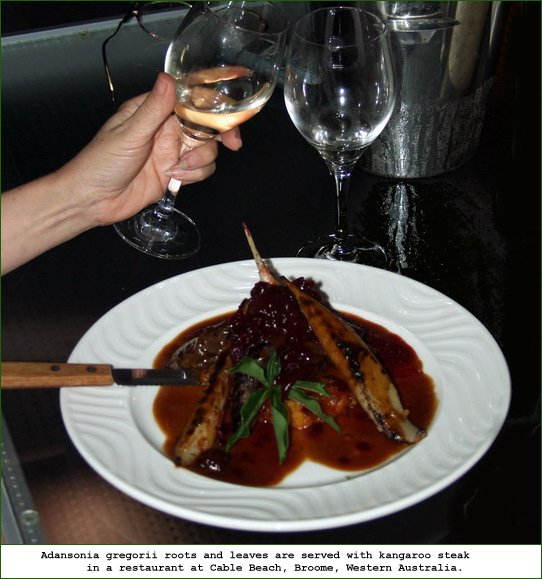

Adansonia gregorii - Boab. The fresh young leaves, fruit, seeds and roots were traditionally eaten. The leaves have a delicate peppery taste and the crisp roots, which taste like radish or water chestnut, can also be cooked. Young Adansonia plants are being trialled by the Department of Agriculture in Western Australia as a new commercial

vegetable crop. The fruit is soft, white and chalky inside with the texture and appearance of meringue, with numerous large seeds, and is very high in vitamin C.

Bombax ceiba var. leiocarpum - The Kapok Tree is a traditional food. Young plants have very fleshy tap roots which can be roasted, with young leaves and fresh flowers used as a spice.

Brachychiton - There is a considerable body of literature that discusses the roots and seeds of Brachychiton populneus as traditional food. However, the species of Brachychiton that are most succulent receive very little attention, even though one would assume these species were also used as a food source. Brachychiton seeds were mostly roasted and ground to make a high energy food.

Brachystelma glabriflorum - Traditional food. Its tuberous stem has been recently identified as a potential new food crop. For more information contact the Australian New Crops website or the Rural Industries Research & Development Corporation.

Bulbine bulbosa and B. glauca - The plant’s tubers and roots were a traditional food.

Bulbs - general - Many australian native bulbs have obvious highly succulent water and food storage organs, usually below the ground. Numerous species were a regular and popular food source for indigenous people e.g. Burchardia was a staple in their diet.

Calandrinia (Parakeelya) - An important food for Aboriginal people. The word Parakeelya was derived from the word ‘periculia’, which is an Aboriginal name for the bread-like seed meal that is made from the cooked seed of Calandrinia balonensis (and possibly C. polyandra). The leaves provide an excellent source of moisture in desert environments and were eaten as a green salad leaf. Over ten species are identified with clear pictures in the picture gallery, to help easily separate them all (including the two mentioned above).

Carpobrotus modestus and C. rossii - The fruit were traditionally eaten.

Dioscorea bulbifera - Round Yam or Cheeky Yam (pictured on page 217 of the book) is a popular and important traditional food. The plant’s tubers were shredded, roasted and soaked for several hours in water before being eaten. They have high water content and vitamin C, with a rather hot, spicy flavour.

They are poisonous if eaten raw, so should be soaked well.

Caution

Care must be taken with any plant that is recognised as a food as sometimes it is only the cooking or preparation that makes it edible.

Also many of the geophytic orchids have tasty sweet bulbs or tubers, but some are rare and all are protected by law.

Dioscorea transversa - Long Yam or Parsnip Yam. The tuber is considered a high energy food source that can be eaten raw.

Disphyma crassifolium subsp. clavellatum - The fresh leaves can be eaten raw or cooked and have a mild salty taste.

Doryanthes excelsa - The roasted roots were a traditional food and the young flower heads were eaten after steaming.

Enchylaena tomentosa - The berry-like fruits are a traditional food.

Anacampseros australiana - The tubers were traditionally eaten.

Mesembryanthemum crystallinum - The seeds and leaves are edible.

Opuntia - Some species have edible fruit and the new stem growth can be sliced and cooked like beans (see also page 222 of the book for more information and pictures of various edible parts of the plant).

Orchids - Most underground orchid tubers were traditionally eaten raw, tasting refreshingly sweet, or were roasted.

Portulaca bicolor - Tuberous roots were traditionally eaten.

Portulaca intraterranea - Traditionally the leaves, stems, roots and seeds were eaten raw or cooked.

Portulaca oleracea - Called Munyeroo, an Aboriginal word (see pages 85-87 of the book for all the different forms of this species), and this was an important staple food and water source, especially in the drier inland. All parts of the plant were either eaten raw or cooked. The tiny seeds were harvested and ground into paste and cooked. P. oleracea is internationally documented as a useful

medicinal and culinary herb with all parts of the plant being used.

It was the most widely eaten native vegetable by early European colonists and inland explorers.

This species is found across the world, with different common names in different countries. In Europe it is widely known as Purslane.

Sarcocornia quinqueflora - This plant (Samphire) is eaten immediately after blanching small lengths of the new growth, or is pickled. It is described as delicious, crunchy and slightly peppery.

Sarcozona - Has sweet juicy fruit.

Suaeda australis - Austral Seablite is recorded as a salty salad vegetable. The leaves can be eaten raw and the young shoots pickled.

Tecticornia verrucosa - This plant produces edible seeds in such abundance that they are still harvested by Aborigines.

Tetragonia implexicoma and Tetragonia decumbens - After rain, fresh new shoots and leaves can be eaten raw. The leaves are best cooked like spinach. A light boiling in fresh water will remove any excess salt. T. implexicoma also has salty, sweet fruit. Numerous pictures which can help identify or separate both these species, and the one below, are available in th larger book titled Australian Succulents- An Introduction.

Tetragonia tetragonoides - This plant (Warrigal Greens) has leaves and fresh shoots that were commonly eaten by early settlers and explorers. It is mostly cooked like spinach. It was introduced to England in 1772, where for many years it was a popular summer vegetable known as Botany Bay Greens. It is the only Australian plant to be grown internationally as a vegetable.

Previous page: Display Gardens

Next page: Seeds, Sale and Care