Australian Succulents

Attila Kapitany

Succulent Orchids

When is an orchid also a succulent?

Numerous dry-tolerant native orchids are also grown by cactus and succulent society members across the country.

Among these are some exceptionally hardy epiphytic and lithophytic species.

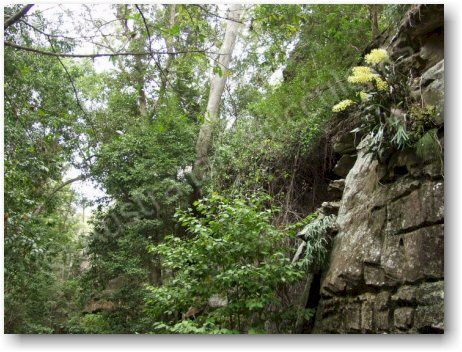

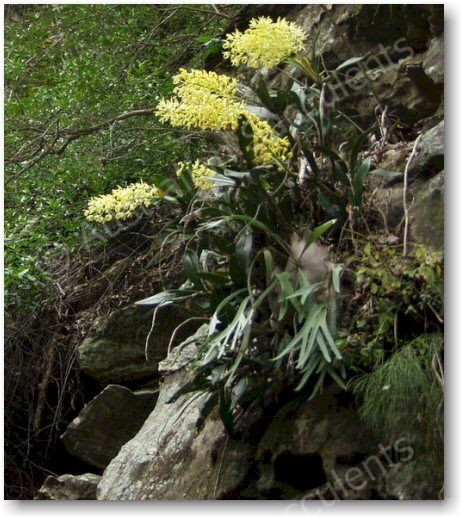

The most notable and well-known of all is Dendrobium speciosum and all its related taxa (now recognised by some authors to be in the new genus Thelychiton).

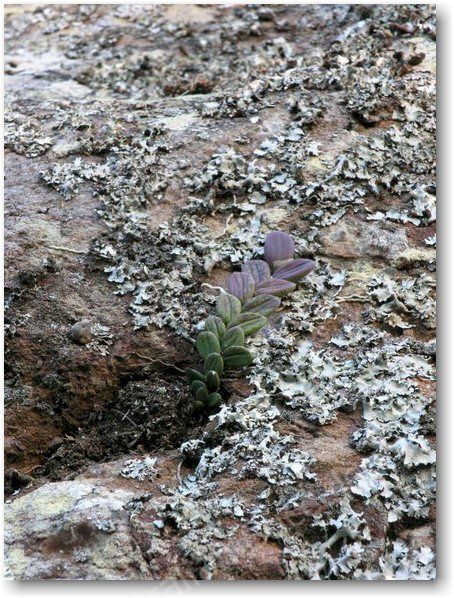

Among this plant’s many common names are Rock Orchid and Rock Lily, It is also well-regarded as an exceptionally hardy rockery plant, and as many gardeners also put their succulents into a rockery, it’s easy to see why the association might be an acceptable one.

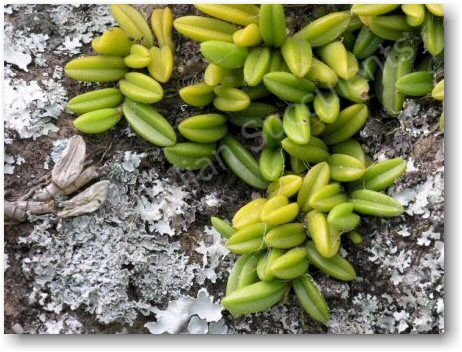

Dendrobium speciosum in typical habitat, growing on exposed rocky surfaces.

Dendrobium speciosum in typical habitat, growing on exposed rocky surfaces, close-up.

The obvious question often arises in discussion about this plant’s relevance in a succulent collection.

Is it really a succulent?

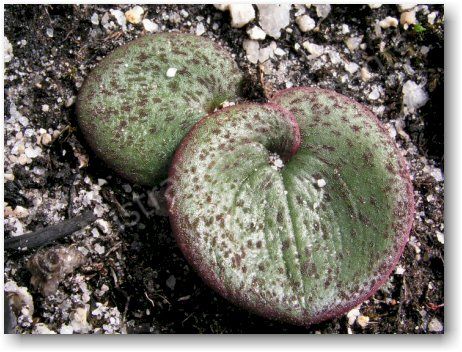

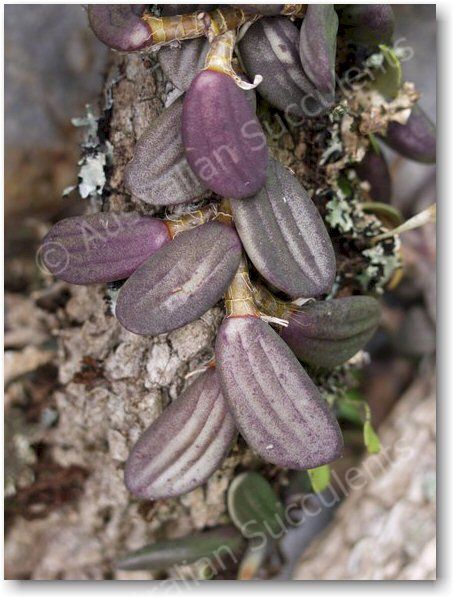

Pyrorchis nigricans – a semi-succulent geophyte with leaves from 40-100 mm in length.

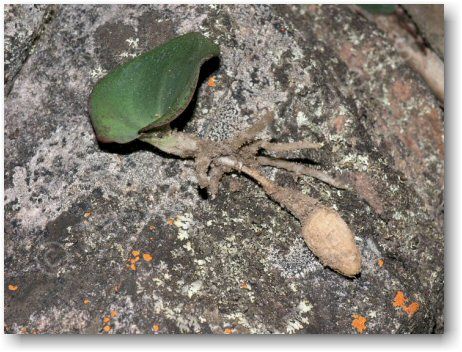

Pyrorchis nigricans showing its exposed succulent tuber.

Just because it grows well amongst them, doesn’t really make it a succulent!

More importantly, at what level of fleshiness or ‘succulence’ does any plant become suitably succulent enough to qualify as a true succulent plant, accepted by all?

A lot of debate goes on about such matters even in scientific circles.

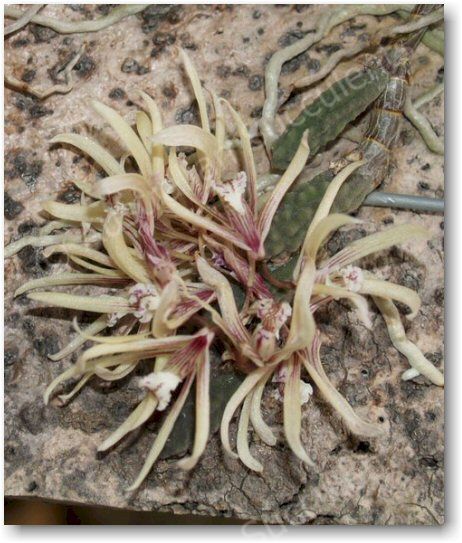

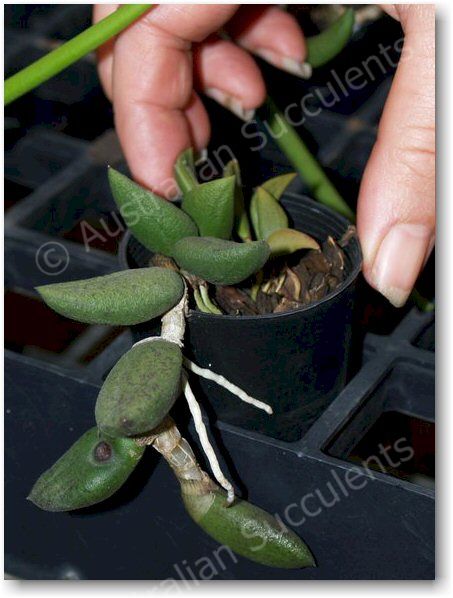

Bulbophyllum shepherdii.

The general accepted criteria for inclusion into any succulent collection is as follows:

- An obvious water-storage capacity in the leaves, stems or roots (or combinations of these).

- Xerophytic qualities - able to survive extended dry periods, without any severe loss of leaves or condition.

- An ability to not only survive, but grow well with minimal food, water and care in cultivation.(usually remaining relatively compact in form)

Interestingly in the Cairns QLD Botanic Gardens, there is a swamp boardwalk leading through parts of the gardens when a large information sign greets visitors.

The sign reads, ‘…..rainforest understorey where succulent plants like Ginger and Alocasia are found..’

While it may be correct to state that such plants are succulent to some degree, these plants would not survive long in the same conditions in which we grow most of our cacti and succulents.

The perennial semi-succulent geophytic orchid, Pyrorchis nigricans usually has a single annual fleshy leaf which grows from a succulent tuber in the cooler months which then dies back to, only the tuber before the drier summer months. There are hundreds of similar orchids in Australia that have very succulent tubers like this; however, they are not generally regarded as succulent plants.

Those xerophytic plants that have evolved swollen water storage organs, above or below the ground, expand and contract as water reserves are stored and used.

After a drought-breaking thunderstorm, a shrivelled or limp plant can expand quickly (in the space of days or weeks) to become turgid and more succulent.

If there are no following rains in the weeks or months after the initial thunderstorm, then these plants will slowly contract as reserves of water are used.

Below are some of the most drought-hardy succulent orchids that can also be considered and grown as succulents.

Bulbophyllum shepherdii

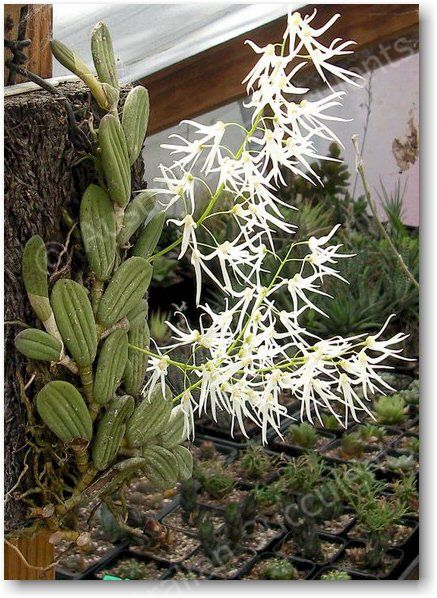

Dendrobium canaliculatum

Dendrobium speciosum

Dockrillia cucumerina

Dockrillia lichenastrum var. lichenastrum

Dockrillia linguiformis

Dockrillia nugentii

Dockrillia rigida

Dockrillia striolata

Dockrillia wassellii

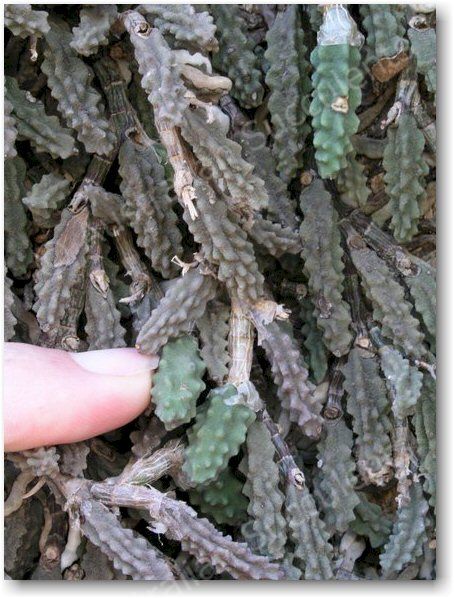

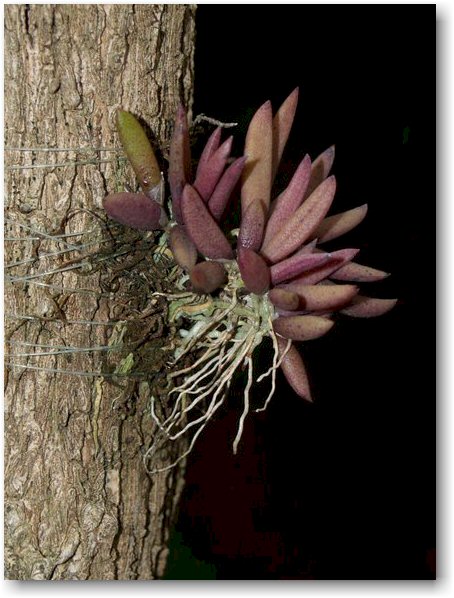

From the above list it becomes obvious that the genus of Australian orchid that most displays succulence and dry-tolerance would most certainly be Dockrillia.

Dockrillia are renowned for having leaves that are greatly reduced, compact, leather-textured or in many cases, with terete (long and circular in cross-section) leaves. Terete leaves are a very common feature of succulent plants around the world.

Dockrillia linguiformis – flowers very readily and heavily in spring.

Dockrillia linguiformis – in habitat its colours are far more dramatic.

Dockrillia linguiformis – growing well attached to a rock.

Dockrillia linguiformis.

Environments with high light intensities produce shorter, more compact and fleshier plants.

The same plants growing in a shady environment are likely to be taller, with larger, thinner leaves.

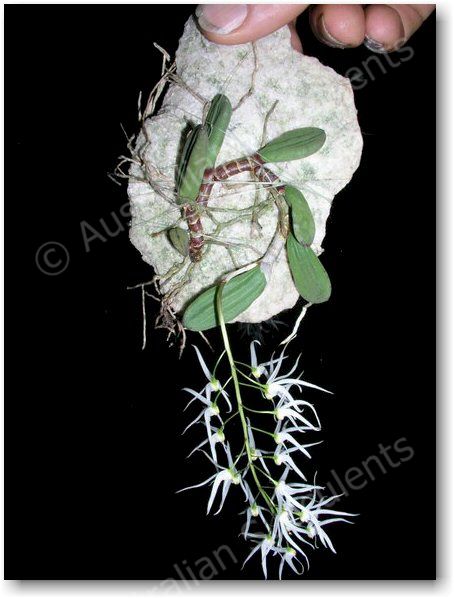

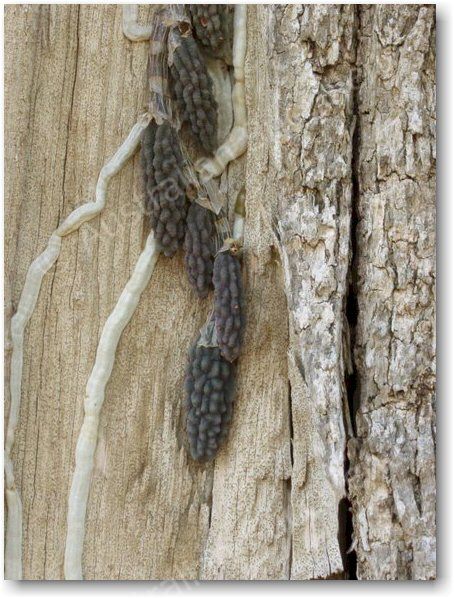

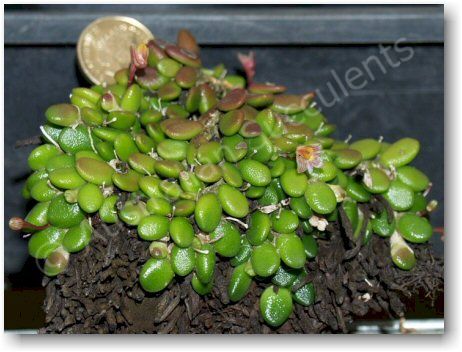

Dockrillia cucumerina – unlike here, in habitat it is usually extremely well-camouflaged against tree bark.

Dockrillia cucumerina – its natural growth is downward-pointing.

Dockrillia cucumerina – flowering in cultivation.

Dockrillia cucumerina – close-up of flowers .

Soils that are very stony, rocky or sandy are usually deficient in nitrogen.

A lack of nitrogen can also result in slow-growing plants with short, stout stems and leaves.

The same plants grown in organically enriched soil would grow rapidly taller and greener.

Dockrillia nugentii.

In concluding this article another relevant point is that the many rocky, exposed habitats where lithophytic orchid species are commonly found are also ideal habitats where a range of other succulent plant genera grow, including Bulbine, Calandrinia, Crassula, Dischidia, Doryanthes, Hoya, Hydnophytum, Myrmecodia, Peperomia and Plectranthus.

Dockrillia lichenastrum var. lichenastrum.

Dockrillia striolata – has very wiry and flexible leaves and stems.

Dockrillia rigida hybrid.

Previous page: New Senecio

Next page: The great prickly pear mystery